The big cost tracking problem of small shows

Published by Quentin on

The BIG cost reporting problem of small shows

The problem

Producing short pieces of content for online outlets is, generally speaking, easier than producing features, TV episodics, or documentaries. Production companies that specialize in this type of content can steadily output between 10 to 30 minutes per day, which is the whole point of this type of operation.

However, this simplicity disappears when we start looking at the budget actualization, expense reconciliation, and overall cost tracking process that is derived from the countless pieces of content produced.

While working for large New Media production companies in Los Angeles, I ran more than once into the “closing of the month” problem. In this recurring situation, a finance partner would ask about the expenses incurred during a specific timeframe with the goal to tie them to the shows in production.

Surprisingly, closing the month was always more difficult than it should have been. Even though our production department had strict budgeting guidelines and extensive control processes to report budget changes and overages, properly actualized budgets were rare, making answering specific finance questions difficult.

Together, I would like to assess the reasons that make this process so complex and offer solutions to simplify this issue.

One budget, multiple shows

When all the elements of a production aren’t perfectly aligned (scripts may not be ready, talent may be unavailable, etc…), you have to become creative and use the crew and equipment you booked to produce something else. You may have to resort to filming two different shows, with nothing in common but the logistics used to produce them.

On features and episodics, the problem is solved by pulling a scene scheduled at a later date. Episodics will sometimes do this across two different episodes of a show, which complexifies the cost reporting a bit, but overall, the amount of manpower available and the slower pace of production (relative to New Media) makes this manageable.

Another frequent phenomenon in New Media is the unforeseen creation of content. It’s possible for a single video to become two episodes once in production. The specific timeframes imposed by television programming don’t exist, making content duration flexible.

So how do you track the individual costs of two separate shows that are produced with the same crew, the same equipment, and the same location?

I like to use the analogy of paint, or, because I have worked on more beauty tutorials than I ever thought would be possible, nail polish:

If you mix two colors of nail polish together, you will get a new color. But once mixed, getting the original colors back is no longer possible. The same goes for budgets: once you make the decision to produce two separate pieces of content with the same resources, it is no longer possible to accurately report the cost of each piece using conventional methods.

Great budgeting tools, bad cost reporting solutions

Budgeting software, spreadsheets, and processes are often designed for budgeting and don’t take into consideration the issue of cost reporting. In addition, operations in the media industry have been built on the back of feature and TV production, which, as we’ve mentioned before, deal with a single budget.

For instance, when you look at a Purchase Order form, it becomes clear that this document was created for the purpose of coding an expense to a singular show. Using the same document to split a bill across multiple budgets isn’t possible because it’s not what it was designed for.

Although technology has evolved tremendously these last few years, the innovations are mostly driven by the needs of Studios. This has benefited set operations for everyone (and we can even argue that small independent productions gained more from the improvements in the camera department than studios) but barely had any impact on the administrative operations for New Media content producers.

To prove this point, one needs only to look at the tools developed by Entertainment Partners over the last few years. Their payroll and budgeting solutions remain to this day lackluster for anyone working on budgets under $50,000.

Lack of data analysis

Although analytical services are widely available on the distribution’s end, combining that data with financial information is seldom put in practice at New Media companies. Again, one of the reasons behind this is simply that it is difficult to accurately report at the individual video level.

Most of the digital content produced for Youtube, Facebook, and other similar distribution platforms fits within a “series” template. When budgeting these series, it is assumed that resources will be used over multiple episodes.

You could argue that the same phenomenon takes place on episodics, but the main difference here is time. A traditional TV show episode takes between 6 and 8 days to film, which gives you a date range to filter your costs by. A Youtube episode can take as little as a few hours, making it impossible to discern between two pieces of content when looking at payroll data.

It’s also worth noting that for a long time, the most popular creative strategy in the New Media industry was to create countless shows until one “stuck”. The extremely low cost of pilot production allowed New Media companies to greenlight indiscriminately, a practice that didn’t reward in-depth performance analysis and cost reporting.

Solving the big cost reporting problem of small shows

The first step towards a solution is to acknowledge the issue. The expected level of cost reporting detail should be made clear before production practices are implemented. From top to bottom, we can report on:

> The amount spent by a creative department as a whole over a period of time

> The amount spent by a unique producer

> The amount spent on a series

> The amount spent on a group of series

> The amount spent on a “round” of episodes

> The amount spent on a single episode

Now that we have a hierarchy of cost reporting, we can start implementing systems to track costs at the level(s) that are interesting to us. If we focus for now on the top three items, we can deduce that we will need identifiers on our production documents that match each level of detail. In other words, you would need some sort of project code broken down as follows:

Department – Producer – Series

Although I am using these three identifiers in conjunction, it is also important to decide whether expenses can be attributed to a single of these elements. Would our producers be allowed to code expenses to a department or producer as a whole rather than to a series? And if so, how will that impact the performance review of the individuals attached?

If we allow expenses to be coded to an individual or department and we use this information to gauge their effectiveness, we tend to encourage practices that go against the spirit of cooperation. For instance, I once calculated that purchasing an asset for a show would save money over renting it. Yet, the proposal was shut down on the basis that the expense would be held against a unique department but the asset would be used by multiple departments.

Of course, this issue could be solved by implementing yet another level of reporting, for expenses that benefit the entire creative team. This is often done for filming equipment purchases but happens at very low interval rates (during the yearly budget review), which leads me to not consider it given our current topic.

Finally, if we know the highest level of expected cost reporting, we can streamline some production operations. For instance, budgeting a series without having to worry about the cost of each episode is a lot faster and easier.

Buckets, budgets, sub budgets…

In the past, I have run into a situation where a “permalance” producer’s salary had to come out of the show they produced. Unfortunately, this strategy didn’t take into account how pre and post-production take place.

During these periods, producers work on multiple shows indiscriminately, making it quite difficult to allocate their salary to a single budget. The solution employed at the time was to code the salary to a different show every two weeks, with as many cycles as needed to last until the contract had ended or the producer became an employee.

Given that these small productions often run budgets under $40,000, this practice would throw off any serious performance review. A better solution to this cost reporting dilemma would be to create a “bucket”, or “sub-budget” (however you like to call it) designed to allocate funds to multiple budgets.

In this example, the producer’s wages for X months would be submitted for approval as a “bucket”, with instructions for the Production Accounting department to split expenses over a specific set of shows. The allocation factor can be revised every time a new show is added to the producer’s slate (and to the bucket) in order to reflect reality.

A simplified version of this practice is to allow for multiple shows to be listed on a Purchase Order or Time Card. However, this supposes that documents are created with this in mind, and that your Payroll partner allows the practice and reports back accurately and always provide employee paystub requirements. Looking for reliable payroll providers? If you own a mid-sized or large company, it is recommendable that you opt for unlimited-access packages to avoid overpaying for the service, you may see this post entitled “how to create paystubs” to learn more!

Weighing the cost and benefits of these practices is important and should be discussed in-depth. In my experience, the clarity gained at the end of the month closing is well worth the additional clerical duties.

Leveraging technology

If we exclude production (as in set related work), it is actually possible to track expenses in great amounts of detail with very basic tools.

A few years ago, I supervised the editorial content production for a Youtube channel. In this type of environment, a team of creative producers, writers, and editors works on a full-time basis across multiple projects.

Given that funding was limited, the pressure to develop shows that performed well was high, which in turn dictated that the amount of detail in cost reporting should allow the leadership team to determine if a single video was worth the expense.

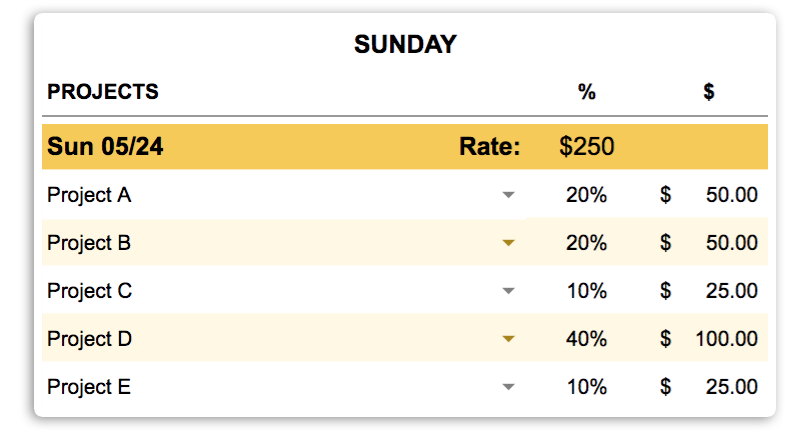

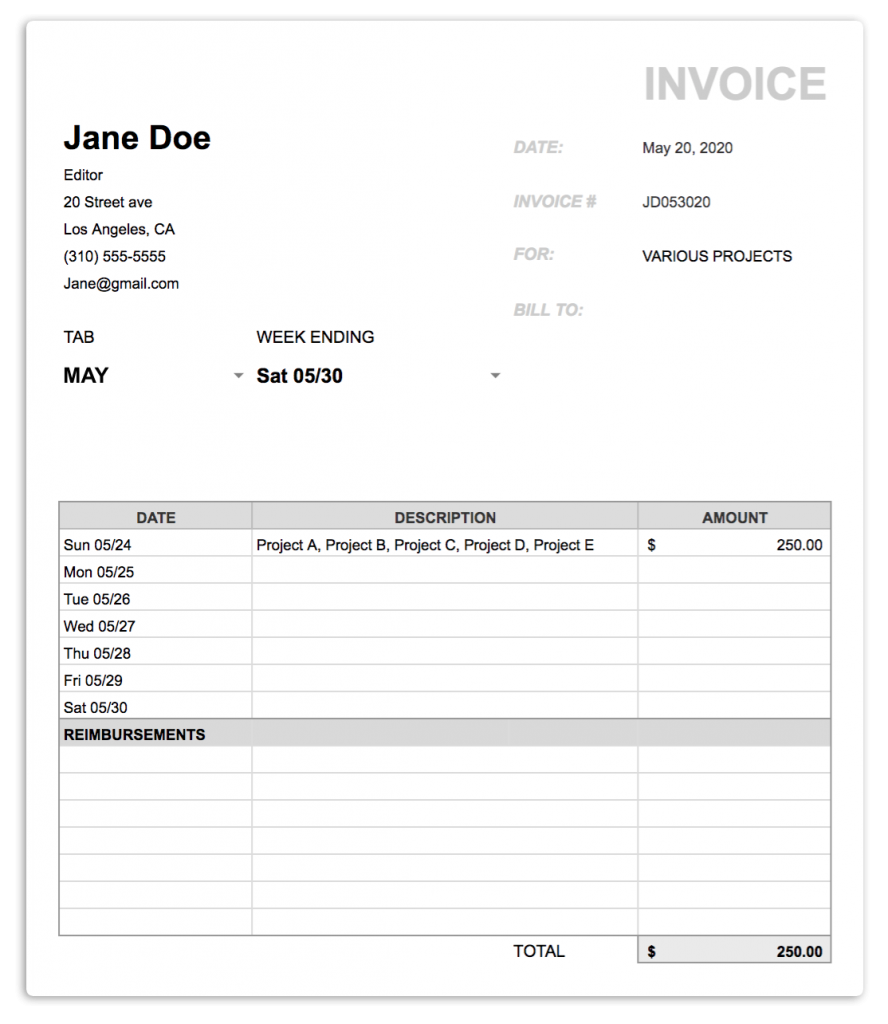

In this situation, I turned to technology in addition to process in order to gather the required data. I created a spreadsheet that allowed each individual to list up to five projects they had worked on every day and to specify in which amounts (50% of the day, 30% of the day, etc…).

Because no one likes doing additional work to get paid, I engineered this system to generate an invoice by the end of the week, using the data provided each day. Since freelancers would have to generate an invoice regardless, this created an incentive to use this system.

The interesting part of this system resides in a different document though. Each freelancer’s spreadsheet feeds into a resource allocation tracker, providing an accurate cost report for each project.

It is possible to engineer better solutions, especially for post-production personnel. You could create a program to:

> Prompt the freelancer to provide their name and rate

> Timestamp when an Avid or FCP project is opened or closed

> Log the name of each project

Doing this would provide you with a fantastic way to track complex expenses without relying on manual input. This comes of course at a price, which should again be weighed against the cost tracking needs.

Working Together

The future of cost reporting will undoubtedly be influenced by the practices in the New Media industry. The problem is much more complex than it ever was in other, more established video production types.

Currently, most production companies approach the problem backward. Whether you are using paint or nail polish, retrieving each original color after they have been mixed together will always remain impossible. For Line Producers, delivering accurate cost reporting once the shows have been mixed is just as impractical.

New media production companies have a fantastic advantage: their own the entire vertical and their size makes cooperation quite simple. Where a studio project’s production team would rarely interact with the distributor, a Line Producer at a New Media company often works in the same building as the editorial calendar’s manager, the performance analyst, the Finance coordinator, etc…

Cost reporting for the sake of cost reporting isn’t useful. Whether your approach is process-driven or relies on technology, one of the keys to success is to work with all the parties impacted by cost reporting in order to define the scope of requirements. This is vital to establish proper measures, which allow us to work faster and deliver valuable metrics that improve the overall quality of our content.